Density is Fun: A Brief History of Zoning in Ann Arbor (Part 2)

Ann Arbor’s zoning history reveals a long-standing pattern of exclusion—from redlining and one-acre lot mandates to modern battles over “neighborhood character.” This article explores how today’s zoning debates echo a legacy of segregation and why embracing density is essential for equity.

This is an on-going series on Density in Ann Arbor

Density might not be the first word that comes to mind when thinking about fun, but it should be! More neighbors mean more energy, more thriving local businesses, and more vibrant communities. This new web series explores how increasing density in Ann Arbor—through better planning, zoning, and housing policies—can make our city more affordable, sustainable, and welcoming. Whether you're a longtime resident, a renter looking for better options, or simply curious about how cities grow, this series will break down why density matters and how we can embrace it for a stronger Ann Arbor.

"Density is Fun" Web Series:

How I Got Here: A Personal Reflection

I attended a City Council meeting where my neighbors came to voice their opposition to the new zoning district for transit corridors, TC1 new zoning designation, TC1. TC1 hopes to create new dense developments in the city along transit corridors. These neighbors expressed their concerns over the changing landscape of Ann Arbor, highlighting building heights, densities, and the “types” of people who might move into these new developments. Their comments could be summed up under the guise of preserving the “neighborhood character” of Ann Arbor.

Speaker after speaker used everything in their arsenal to reject this map overlay amendment. They said that Ann Arbor was not Detroit. They said that Ann Arbor is a funky artist haven and that greedy developers would ruin the city’s vibe. They talked about their housing values. They talked about parking on “their” street. They talked about how these future developments would be so high as to blot out the sun. Some neighbors were so bold—without any sense of shame—as to say, “Ann Arbor is closed.”

But underneath the surface of these arguments—about vibes, about parking, about shadows and sun—was something deeper, more unsettling. What they were really saying was that change itself was unwelcome, especially change that would invite new people into “their” neighborhoods. The fear wasn’t just about buildings; it was about who would live in them. It was about the loss of control, the end of homogeneity, the disruption of comfort. And as each comment unfolded, it became clearer that the battle over housing was also a battle over belonging.

Over and over, I heard a disturbing pattern: “We don’t want more neighbors. We don’t want more housing.” Then, with a seamless shift, those same speakers would turn to City Council and say, essentially, “We elected you to protect this—to enact exclusionary policies that preserve our way of living, our neighborhood character, our homes, our sense of place. And if you don’t, we’ll vote you out and replace you with someone who will.” That transition—from fear to political demand—was striking. It revealed how exclusionary views weren’t just personal preferences; they were being weaponized through the democratic process to lock others out.

Then my neighbors started to use dog whistles in their comments to block the amendment change, which prompted me to tweet.

I’m still processing hearing my neighbors use dog whistles about Ann Arbor. Like Ann Arbor is full move to Detroit. Or hearing my neighbors say to #a2council, we hold these exclusionary views & we elected you to enact them through policies & laws. Not much has changed after all. pic.twitter.com/rATnmwlxH7

— Donnell Wyche (@donnell) November 11, 2022

In my tweet about the issue, I also shared an article from 1970 that reflected similar sentiments. Ann Arbor has been having the same conversation for the past 55 years: Is there space in Ann Arbor for everyone? In 1970, the answer was no—especially not for “the Negros.” Residents at the council meeting then suggested that their elected officials restrict plots to one acre in hopes of excluding Black people from the city. Fifty-five years later, we are still debating the same issues. To say that Ann Arbor is progressive, welcoming, inclusive, and equitable seems more like an aspiration than a reality.

My neighbors concluded their comments by using the duplicitous phrase, “neighborhood character.” On the surface, the phrase evokes emotion and a vague sense of community that comes with geographic proximity—visions of kids playing in the street, neighbors greeting each other on the stoop, sharing resources, and looking out for one another. In this beatific vision, greedy developers are unleashed to destroy this treasured possession. When the phrase “neighborhood character” is invoked, the speaker often speaks from nostalgia—a desire for Ann Arbor to remain a small, quaint, eccentric Midwestern town. But in reality, it is a dog whistle. It’s flowery language designed to conceal its true intent: racism, classism, and other forms of discrimination; the freezing of a place; the lock-in of its value to the current occupants; and the goal of excluding others.

Zoning as a Tool for Segregation

The sentiments expressed at that council meeting are not new—they are part of a much longer story about who is allowed to belong in Ann Arbor. While the language has become more coded, the impact remains the same. Beneath the surface of debates over height limits, parking, and “neighborhood character” lies a legacy of exclusion that has been reinforced for decades through planning and policy decisions. To understand how we got here, we have to look at the tools that have been used to shape who gets to live where—and who doesn’t.

Ann Arbor’s zoning policies reflected national patterns of racial and economic segregation. Redlining and deed restrictions explicitly barred Black families from certain neighborhoods well into the mid-20th century. Even after legal segregation ended, zoning laws served the same purpose:

- Single-family zoning kept lower-income families (disproportionately Black and brown) out of wealthier neighborhoods.

- Minimum lot sizes and parking requirements made housing more expensive and less accessible.

- Limited multifamily zoning ensured that affordable housing options were scarce.

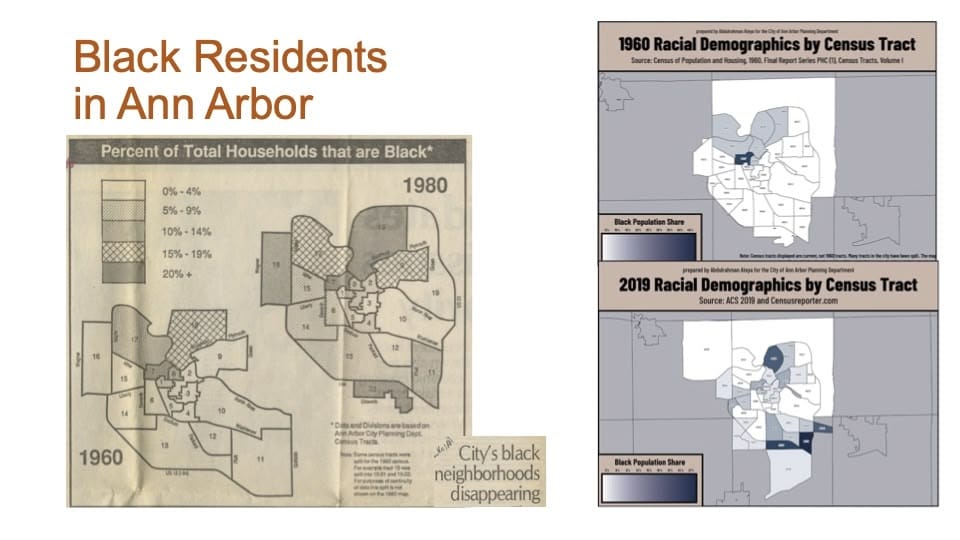

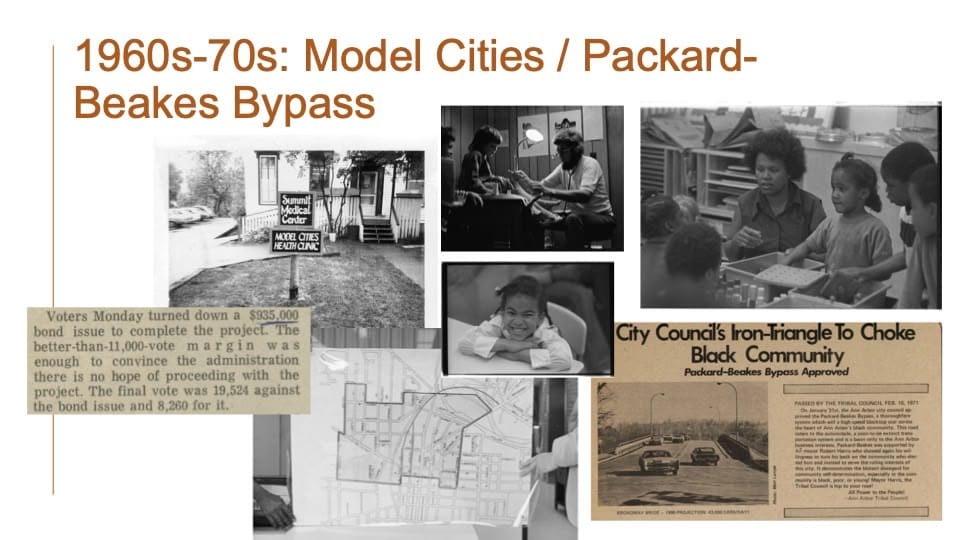

Historically, Ann Arbor actively participated in urban renewal efforts that targeted Black communities for demolition and redevelopment. Residents of the historically Black neighborhoods north of downtown recall how their homes were seized under the justification of "slum clearance," only for the land to be redeveloped into high-end housing. A Black community once existed in the heart of Ann Arbor; today, it has been almost entirely displaced due to these policies.

Echoes of the Past in Present-Day Land Use Debates

The arguments used to justify exclusionary zoning in the past are eerily similar to those used today. In the 1970s, Ann Arbor landowners openly admitted that they supported large minimum lot sizes—such as one-acre zoning requirements—to make land unaffordable for Black residents. As former City Council representative LeRoy A. Cappaert noted, some voters opposed annexation efforts because "they desired large one-acre lots which would be too expensive for Negroes to purchase." This was an intentional use of zoning to keep Black families from owning property in Ann Arbor.

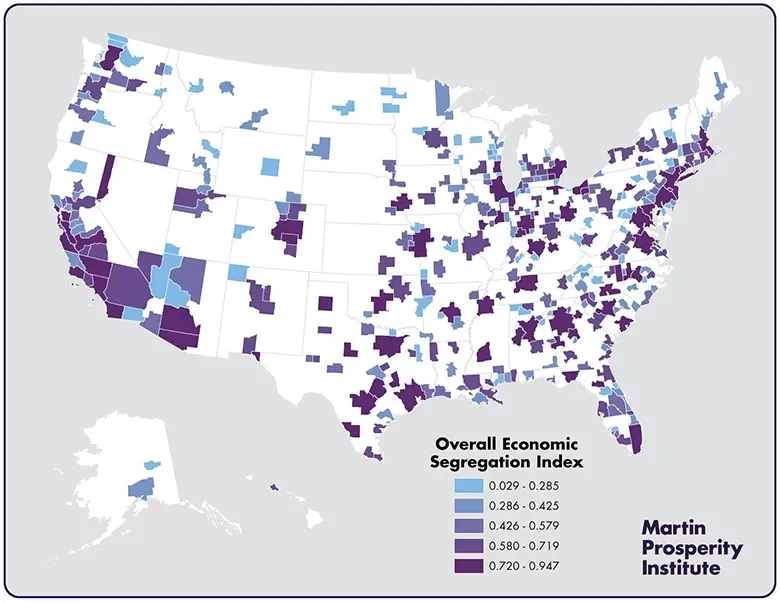

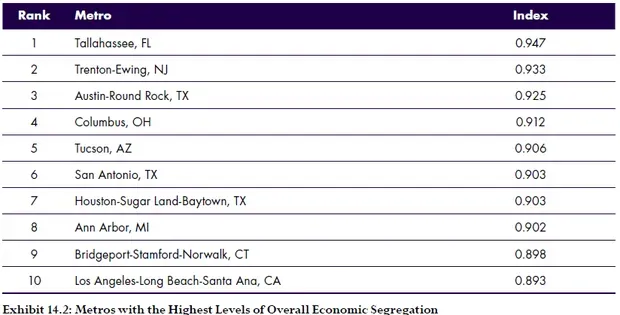

Economic segregation isn’t just a theory—it’s measurable, and Ann Arbor ranks among the most economically segregated metros in the U.S. According to a study by the Martin Prosperity Institute, our city is 8th in the nation for overall economic segregation, with wealthier, highly educated residents clustering in certain areas while lower-income populations are pushed out. (See the full report here.) This is a direct consequence of exclusionary zoning, which limits where and how diverse types of housing can be built. If we want an Ann Arbor for everyone, we need policies that don’t just preserve exclusivity but actively foster economic diversity.

Fast-forward to today, and the same exclusionary logic persists. Many current landowners push back against zoning reforms that would allow duplexes, townhomes, missing middle housing, or smaller lot sizes, citing concerns about "neighborhood character" or "property values." But at its core, this resistance serves the same function it did decades ago: keeping housing scarce, prices high, and new (often lower-income) residents out.

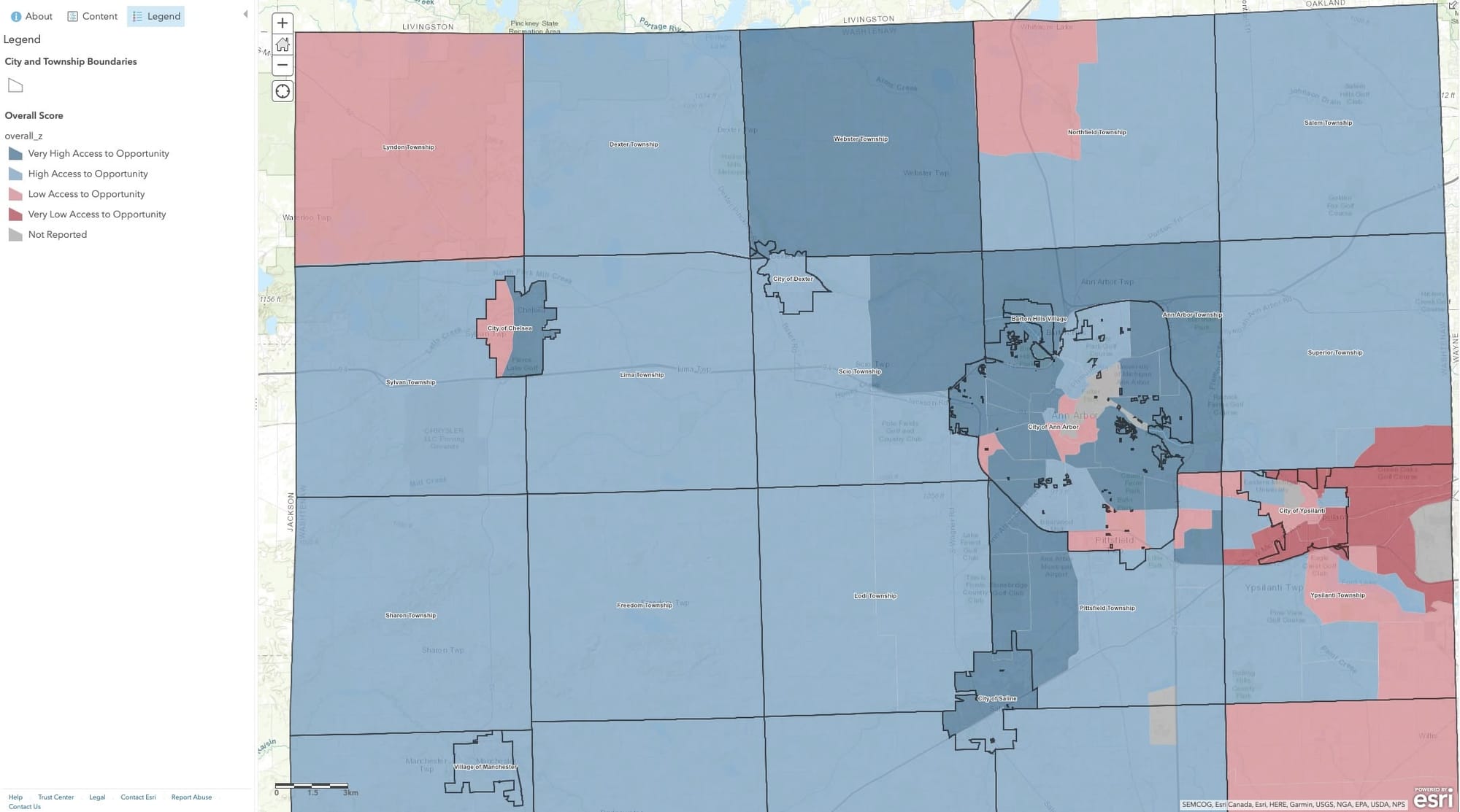

The Washtenaw Opportunity Index is a crucial tool for understanding how structural privilege and economic barriers shape access to housing, education, employment, and community resources. It measures disparities across the county, revealing how race and geography continue to determine life outcomes. Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, for example, remain deeply divided by opportunity, a legacy of exclusionary zoning and discriminatory housing policies. The Index assigns opportunity scores based on factors like health outcomes, job access, education levels, and economic well-being, highlighting stark contrasts between high-opportunity and low-opportunity areas.

Recent Zoning Reforms and the Comprehensive Plan (2000s-Present)

Recognizing that restrictive zoning contributes to the housing crisis, Ann Arbor has begun taking incremental steps to reform its land-use policies. While significant changes are still needed, these steps demonstrate a growing awareness of the problem.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)

- In 2016, Ann Arbor legalized ADUs (sometimes called granny flats or backyard cottages) in an effort to create more housing options within single-family neighborhoods.

- However, the regulations were highly restrictive, limiting where and how ADUs could be built. Only in 2021 did the city relax these rules to make ADUs a more viable housing option.

- Since 2016, about 50 applications for ADUs have been submitted.

Transit-Oriented Zoning & Parking Reform

- In 2023, the city eliminated minimum parking requirements for new developments, allowing builders to create more housing without being required to include costly, space-consuming parking lots.

- This reform encourages walkability and transit use, making it easier to build near bus and train lines.

- Transit-oriented zoning changes allow more multifamily housing near transit corridors, a crucial step toward increasing density in strategic locations.

Eliminating Exclusionary Zoning

- One of the biggest reforms under discussion is eliminating exclusionary zoning, which currently prevents duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings from being built in most of the city.

- Cities like Minneapolis and Portland have already made this change, and Ann Arbor is considering similar steps as part of its Comprehensive Plan update.

- If implemented, this reform could significantly increase housing diversity and affordability, making Ann Arbor more accessible to people of all income levels.

Why This Matters for Density

Zoning restrictions don’t just impact housing affordability—they also shape the very fabric of our communities.

Without zoning reform, Ann Arbor risks becoming a city where only the wealthy can afford to live. Workers, teachers, nurses, service employees, and even many University of Michigan staff members are being priced out, forced to live in surrounding communities and commute long distances.

As Jennifer Hall, executive director of the Ann Arbor Housing Commission, has said:

“If you talk to a Black resident of Ann Arbor in their 60s or 70s, they’ll remember a time when deed restrictions explicitly barred non-white individuals from owning or living in certain properties—unless they were domestic workers. As a result, the neighborhoods we see today remain segregated—primarily by income and, to a lesser degree, still by race. This is a direct consequence of that history. If we are serious about making housing policy, we must acknowledge and address this legacy of segregation.”

A city that prioritizes density and housing accessibility can:

- Reduce displacement by making room for people of all incomes.

- Support local businesses with a larger customer base.

- Encourage sustainable development by reducing car dependency and urban sprawl.

- Foster stronger communities by allowing people to live closer to where they work, learn, and gather.

- Increase access to opportunity by ensuring that people of all incomes can live near jobs, schools, and essential services, reducing barriers to economic mobility and social equity.

The history of zoning in Ann Arbor has been shaped by exclusionary policies—but the future doesn’t have to be. If we want to build a more welcoming, affordable, and connected city, embracing density is not just an option—it’s a necessity.

Looking Ahead: The Path to a More Inclusive Ann Arbor

The Comprehensive Plan update currently underway presents a unique opportunity to rethink how zoning shapes Ann Arbor’s future. This is our chance to:

- End exclusionary zoning—zoning laws that restrict what types of homes can be built in an area, often limiting housing to single-family homes and excluding more affordable options. These rules have a long and troubling history of reinforcing racial and economic segregation. (The Racist History of Single-Family Home Zoning.)

- Allow homes near destinations and bus lines to create walkable, bike-friendly communities.

- Increase affordability and reduce displacement by allowing more diverse housing options citywide, fostering mixed-income neighborhoods instead of pricing out middle- and lower-income residents.

- Acknowledge and address past injustices by prioritizing policies that reverse the harm caused by exclusionary zoning.

For too long, the argument against building affordable or multi-family housing in certain neighborhoods has echoed a modern version of “separate but equal.” It suggests that apartments, townhomes, and denser housing are fine—just not here, not in my neighborhood. But just as separate was never truly equal in the past, it still isn’t today. Segregating housing types by neighborhood only reinforces racial and economic divides, limiting opportunity and deepening inequality across our city.

If we truly want Ann Arbor to be a city that welcomes everyone, an Ann Arbor for all, we must move beyond the restrictive and exclusionary zoning policies of the past and embrace a future where density is fun—and necessary.

Up Next: The Comprehensive Plan – What It Is and Why It Matters

In the next installment, we’ll take a closer look at the Comprehensive Plan update—Ann Arbor’s roadmap for future growth and development. We’ll explore why this document matters, how it shapes everything from housing to transportation, and what’s at stake if we don’t get it right.