Density is Fun: A Brief History of Zoning in Ann Arbor (Part 1)

Ann Arbor’s zoning history reveals how land use policies have shaped who can live here. From racial redlining and deed restrictions to one-acre lot mandates that priced out Black families, zoning has long been a tool for exclusion. Today’s zoning debates echo these past tactics.

This is an on-going series on Density in Ann Arbor

Density might not be the first word that comes to mind when thinking about fun, but it should be! More neighbors mean more energy, more thriving local businesses, and more vibrant communities. This new web series explores how increasing density in Ann Arbor—through better planning, zoning, and housing policies—can make our city more affordable, sustainable, and welcoming. Whether you're a longtime resident, a renter looking for better options, or simply curious about how cities grow, this series will break down why density matters and how we can embrace it for a stronger Ann Arbor.

Introduction: Why Zoning Matters

Zoning shapes the way cities grow—what can be built, where, and for whom. While it might seem like a neutral tool for organizing land use, zoning has often been used to restrict growth, enforce segregation, and limit housing options. Ann Arbor is no exception. Understanding our city's zoning history helps us see how past decisions have created today’s housing challenges and why reform is necessary for a more inclusive future.

Jennifer Hall, Executive Director of the Ann Arbor Housing Commission, highlights how past zoning and housing policies have shaped the city’s current segregation and why addressing this history is crucial for equitable housing reform:

"If you talk to a Black resident of Ann Arbor in their 60s or 70s, they’ll remember a time when deed restrictions explicitly barred non-white individuals from owning or living in certain properties—unless they were domestic workers. They can recall redlining. These discriminatory practices weren’t that long ago in our history. As a result, the neighborhoods we see today remain segregated—primarily by income and, to a lesser degree, still by race. This is a direct consequence of that history. If we are serious about making housing policy, we must acknowledge and address this legacy of segregation."

How I Got Here: A Personal Reflection

The issues of income inequality and income disparity are close and personal for me. I was born and raised in the inner city of Washington, DC, our nation’s capital. I grew up in the Southeastern DC neighborhood known as Anacostia. This neighborhood is adjacent to the Capitol, but is separated physically by the Anacostia River, separated economically by its poverty, and separated racially by its lack of diversity. This neighborhood was home to the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who was the first African American to break the racial barrier and purchase a home in the community.

As I grew up in this community, over 20% of the inhabitants were unemployed and over 50% of the kids lived in poverty, so having and keeping a job was a struggle. My mom was a working single mother who had to take multiple buses to get to work because there was no access to the Metro on our side of the river at the time. Given the limited transportation options, my mom had to leave early, often taking multiple buses to arrive at work on time—forcing me, as a five-year-old, to become a latchkey kid.

My mom was denied what I now take for granted: being able to walk my daughter to school. When I walk my daughter to school, I get to see my neighbors on a daily basis. I see my daughter’s classmates as they are walking to school. When I get to school, I greet her teachers. I am able to volunteer weekly in my daughter’s class, helping her and her classmates learn to read. Each of these experiences creates a greater sense of belonging for me and my daughter.

One of the reasons I can have this experience is because I work and live in my community, and our school is in our neighborhood.

Shouldn’t everyone be able to have that same sense of belonging? The same opportunity to connect with their family and community? But when you have to live thirty minutes, forty-five minutes, an hour away from where you work—because you cannot afford to live in that same community—that eats into your ability to be connected in your community. So my vision for Ann Arbor is that everyone who works here and wants to live here can have the same opportunities I have.

We should find a way to make this happen because density is fun! Before we get to the density, let's talk about zoning, what it is and where it came from.

What is Zoning? Where Did It Come From?

Zoning as a legal concept emerged in the early 20th century, largely driven by efforts to regulate land use and property values. However, it was also deeply entangled with racial segregation. After the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision struck down explicit racial zoning laws, city planners and federal officials sought alternative methods to maintain racial segregation under the guise of economic and land-use regulations.

In 1921, President Warren G. Harding’s Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, formed an Advisory Committee on Zoning, which distributed a model zoning ordinance to cities nationwide. The committee publicly framed zoning as a tool for urban organization, but its members—many of whom were segregationists—understood its potential to shape racially exclusive neighborhoods. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., a key figure in American city planning, argued that racial divisions were essential to successful housing developments, warning that forcing racial integration would be economically detrimental. Similarly, Alfred Bettman, another influential zoning advocate, emphasized zoning’s role in “maintaining the nation and the race.”

By 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Boards formalized this segregationist approach, adopting a code of ethics instructing realtors never to introduce people of “any race or nationality” into neighborhoods where their presence might lower property values. Columbia Law professor Ernst Freund later noted that maintaining racial homogeneity was a more powerful driver of zoning’s expansion than even single-family districts.

As Richard Rothstein explains in The Color of Law, early zoning policies were designed to be legally sustainable methods of racial exclusion.

“Because the Buchanan decision had made it impossible to find an appropriate legal formula for segregation,” Rothstein writes, “zoning masquerading as an economic measure was the most reasonable means of accomplishing the same end.”

Ann Arbor Before Zoning (1824-1923)

For nearly a century, Ann Arbor had no zoning laws. The city developed organically, with a mix of homes, businesses, and industrial uses coexisting. This unregulated growth allowed for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods—the kind many cities now try to replicate. However, as Ann Arbor expanded, pressure grew to impose zoning rules to control land use, property values, and neighborhood composition.

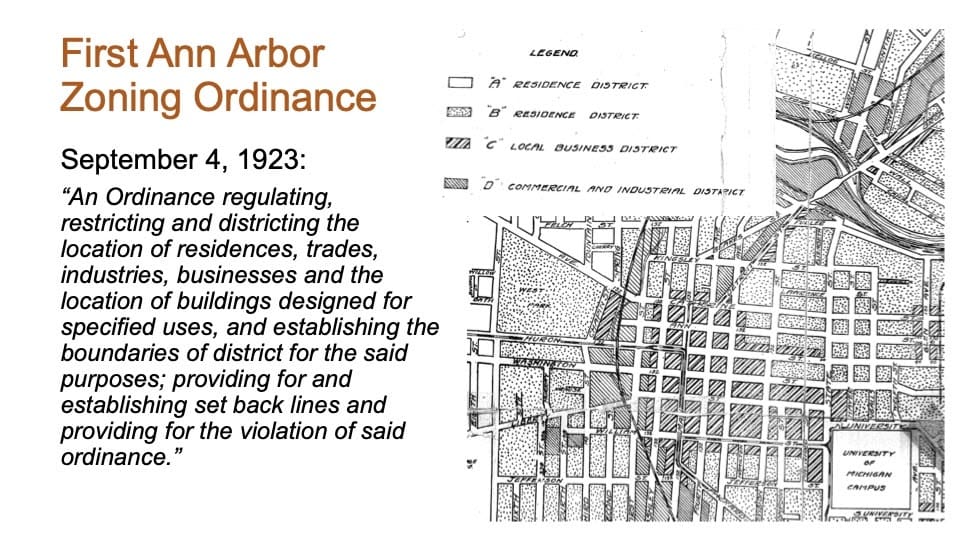

The First Zoning Ordinance (1923)

In 1923, Ann Arbor adopted its first zoning ordinance, just a year before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of zoning in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. This ordinance:

- Created four zoning districts (residential, commercial, industrial, and unrestricted).

- Introduced setback requirements for buildings.

- Regulated the location of housing and businesses.

At just seven pages long, the 1923 zoning code was readable and straightforward. Over the next century, however, zoning in Ann Arbor would become far more complex—and far more restrictive.

Post-War Zoning and the Rise of Exclusionary Policies (1950s-1980s)

The mid-20th century saw zoning evolve into a tool for exclusion. Several key changes reshaped Ann Arbor’s housing landscape:

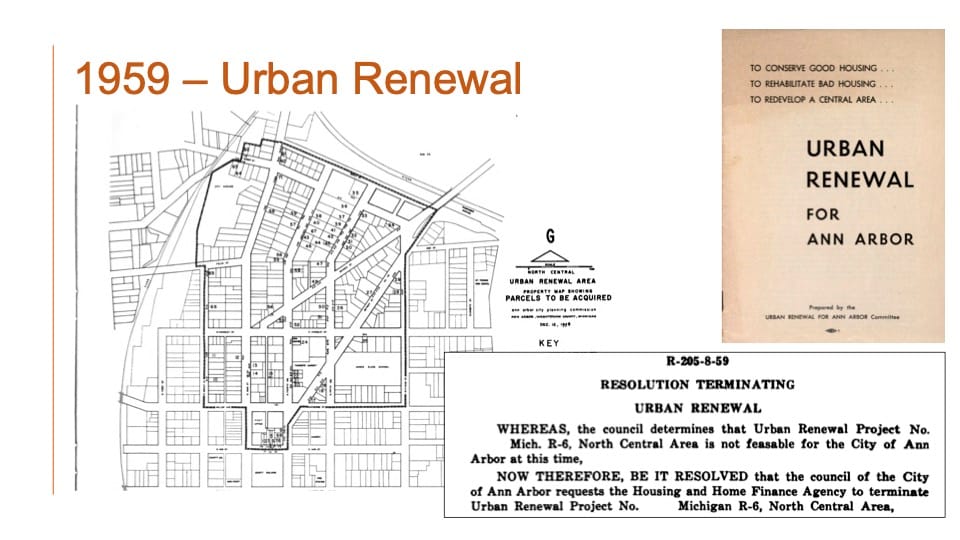

- 1940s-50s: Urban Renewal & Displacement

- Federal policies encouraged cities to clear "blighted" areas, disproportionately impacting Black communities.

- Ann Arbor followed national trends, using zoning and redevelopment to push lower-income residents out of downtown areas.

- The proposed Packard-Beakes Bypass was designed to cut through Ann Arbor’s Black community, disrupting neighborhoods under the guise of traffic improvement. Though the project was eventually halted, the damage had been done—many Black families were displaced, and the city had already acquired properties through eminent domain, fracturing the social fabric of the community.

Shirley Beckley, now 82, witnessed this firsthand when the city forced her family to leave their home at 115 W. Kingsley Street in the late 1960s. "It was traumatic," Beckley recalls. "We didn't have a choice." The city paid just $10,000 for her family home—a property where luxury condos now sell for over $1 million.

This pattern of displacement eventually unraveled what had been a tight-knit Black community, with many residents unable to afford housing elsewhere in Ann Arbor as prices rose.

1957: The Expansion of Zoning

- The zoning code grew to 67 pages and added 16 zoning districts, increasing regulation.

- Lot size minimums were introduced, limiting density and making housing less affordable.

- 1960s-70s: Suburbanization & Exclusionary Zoning

- Ann Arbor neighborhoods used zoning to block apartments and multifamily housing. This is the origin story of the Old West Side Historic District.

- Duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings were effectively banned in many areas.

- Historic districts were created, limiting new development in key areas.

By 1980, Ann Arbor had 33 zoning districts and a 202-page zoning code, reflecting a shift from flexibility to restriction. Zoning exists for a reason—but the reason matters. It has been wielded both as a tool of community planning and as a barrier to inclusion.

This history of restrictive zoning has direct consequences for Ann Arbor today. The city is now exploring adding 35,000 to 40,000 new households to accommodate approximately half of the workers who currently commute into the city. Community sentiment appears to be shifting, with 75% of participants in recent planning workshops supporting more duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes in traditionally single-family neighborhoods. Today, as Ann Arbor faces a housing crisis, we must decide whether to continue using zoning to exclude or to reimagine it as a means of creating a more just and welcoming city. The choice is ours: Will we embrace change and build a future that allows more people to call Ann Arbor home, or will we let outdated policies dictate who belongs?

In Part 2 of A Brief History of Zoning in Ann Arbor, we will explore how these historical zoning decisions continue to shape Ann Arbor today and what we can do to move toward a more inclusive, sustainable city. Stay tuned!